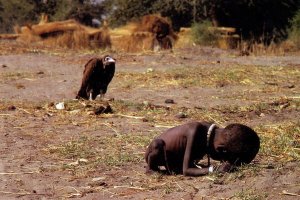

MAMA AFRIKA: Finbarr O’Reilly’s depiction of famine-stricken Africa won him World Press Photo in 2006. COURTESY: Finbarr O’Reilly/ World Press Photos

There’s something exhilirating in holding your first camera. You feel invincible. People in front of the lens may be smiling, crying, shaking or playing, but you are absolutely still and focused. You wait and watch. There you see it – that split second that makes the photo stand out above the rest. Click.

Content, you take it home and watch it over and over again on your PC screen. It has a unique story; maybe it was the last tear drop escaping a child’s face as she fell. Or, maybe it was the smile she had as she realised her ice-cream escaped the fall unscathed.

Johann van Tonder, photojournalism lecturer at Stellenbosch University’s Journalism Department, lists the three characteristics that set photojournalism apart: a subject, a subject which stands out and a story told by the picture.

Often, people mistake photojournalism with art. You may take a pretty picture of a child, an insect or a flower, but if it doesn’t tell a story, it is NOT photojournalism.

The best photojournalism picture often has a heart beat. It is able to speak to the viewer. It even has the power to move, intrigue or disgust him/her.

The Bang Bang Club by South Africans Joao Silva and Greg Marinovich captures the thrill, pain and glory (or lack of it) photojournalists go through. Their friend, Kevin Carter, won a Pulitzer prize for his photo of a child stalked by a vulture in famine-ridden Sudan. He was criticized for being insensitive. People in his own profession called him a coward for taking the picture, rather than helping the child. He became increasingly depressed and eventually committed suicide. As Marinovich points out in the book: “That image is engraved and burnt into your mind forever.”

GENIUS: James Nachtwey covered the Bosnian war, amongst others. His black & white technique proved that composition can be more powerful than colour. COURTESY: James Nachtwey

James Nachtwey has similar views in a National Geographic documentary made about him and his work. Nachtwey has been to some of the most war-ridden places in the world. His experiences in Bosnia turned him into an insomniac and recluse. He couldn’t confide in his wife or children. He found solace in taking even more horrific pictures. When his skin began to melt while taking a picture of an explosion, he realised his obsession with the right shot and addiction in getting it was taking over his life.

“Nothing prepares you for the pain afterwards,” says a former Zimbabwean photojournalist. His PC is filled with images of bruised bodies and raw flesh; after ZANU-PF officials threatened him and his colleagues as they tried to get rid of journalists in Zimbabwe.

They were harrassed and beaten; their camera straps used to strangle them.

There’s a price to pay for being a serious photojournalist. It demands determination and courage. It includes long hours, days or years of being in threatening places for a few published pictures. But the best photojournalists know that there is power in their profession. It is the power to paint a more realistic world, one defined by the eyes which were brave enough to look first.